Embedded Practice and the Future of (Art) Work - Andy Abbot Part 3

- Andy Abbott

- Mar 1, 2021

- 9 min read

Updated: Mar 23, 2023

The Residential Approach

A potential challenge with co-produced, site-responsive and socially engaged methods, not to mention embedded practice, is the extra time and resources required to do it properly. Whilst it may seem convenient to open up the pool of potential collaborators to the public – is a socially engaged artist just someone that gets the audience to make the work for them? – the process to do this in a rigorous and careful manner is slow and time-consuming.

The publication of Nicolas Bourriaud’s key text on art and the social ‘Relational Aesthetics’ in the 1990s prompted a lengthy and protracted debate within contemporary art circles about the stakes for participation in art and social practice that continues today. On one side writers and critics including Grant Kester and Maria Lind demanded that artists consider the inherently political dimension of participation and collaboration in their practice. The other side, most associated with critic Clare Bishop, argued for a more autonomous reading of art that maintained its function to be disruptive or antagonistic and therefore not judged alone on its ethics.

Regardless of whether it is evaluated by the quality of the outputs, or by the quality of the experience for those that participate in its making, the fact remains that a certain amount of time and energy is required to make ‘good’ participatory art. Embedded practice adds an additional layer to this demand by forcing a consideration of the long-term benefits or effects of the artistic intervention: its ability to meaningfully add value to what already exists and may come afterwards.

As an artist working in this field then, there is undoubted pressure to ‘know the field’ before making any rash and potentially wasteful, perhaps even harmful, artistic moves. The residency model, that In-Situ has used historically, allows time for an artist to do this orientation over a loosely fixed period without pressure to produce agreed outcomes. The assumption or hope being that in so doing the artist will arrive at a project, or more likely a proposal for a project, that has been developed authentically in response to their time in place.

This, however, raises further questions about how much research is enough, when is the appropriate time to move into the ‘delivery phase’, and where the responsibility of the long-term impact or legacy of the project lies. Is it with the artist or the organization? If it is with the artist then does that necessarily mean that artists can, or should, only be working in places in which they themselves are embedded – where they live? Or, if the responsibility lies with the organisation that invites outsiders to work in their place, then how much time, resource and support is appropriate or expected, and how best to manage the risk of disruption, challenging questions and ‘fresh perspective’ that such a process may pose?

Yvonne Carmichael and Andy Abbott Cittadellarte, Biella 2006

I have experience on both sides of the arrangement: as artist and organizer. As an artist I had completed a few research-based residencies of various lengths. For example, the four-month UNIDEE programme at Michelangelo Pistoletto’s Cittadellarte centre for ‘art for the responsible transformation of society’ in another former mill of a textiles town, Biella in Northern Italy. I was invited to be a resident in collaboration with my partner Yvonne Carmichael in 2006, which resulted in a longer term textiles towns twinning project for the subsequent year. Or the five-week residency that I undertook for PiST in Istanbul in 2013, in which most of the engagement, research and artistic production took place in the time-scale of the residency but the themes and research of project (a postwork utopia) I am still working with today.

Practically all my commissioned projects have required me to learn about, respond and engage with a place and its people. Some have required I do this very quickly and others over a longer period of time. In some cases I have been asked to work with an existing archive, specific group, or set of organisations such as the Wakefield Arts Partnership who tasked me to research Hidden Wakefield in 2016. Others have been purely self-directed endeavour that have required me to find me feet and make connections independently. In 2018 I undertook a ‘digital residency’ for the Museum of Oxford where there was little expectation for me to be present in place whatsoever.

Working as part of an artist-led collective, as well as being involved in the Do-It-Yourself music scene, meant that my practice had come to encompass arts organization as much as making. Often it was the only way to make things happen. This led me to, between 2015 and 2018, pilot a Centre for Socially Applied Arts for the University of Bradford through which I produced a programme of exhibitions, events and projects by artists and curators with research-led, interdisciplinary and socially impactful practices. Working with limited resources and support, my role there was to develop and help realize projects that would respond to the specific and often complex context of a technical University in a postindustrial, multicultural city.

Through these experiences I have learned that there is no one method, structure, or even amount of time to guarantee a successful or impactful socially engaged project. Whilst it would seem intuitive that the longer time-scale open-ended process would always create a better work, sometimes the artist tasked to make a quick and insightful ‘intervention’ can - with the appropriate support from an organization ‘on the ground’ - result in a project that positively shakes things up and resonates with audiences. Conversely, when organizations offer too much support or guidance this can be a restrictive act in which nobody gets what they needed.

The challenge, then, is not necessarily how to generate endless time and resources (time after all is a luxury that increasingly fewer of us have), but rather how to make good use of the time and resource available, and draw upon more if required. The responsibility of the artist is to know what they are capable of achieving within the time allotted to them – even if this is with an open outcome – and make transparent decisions that will ensure the best use of that time. As for the organization: they are in the best position to provide the infrastructure required for the artist to make a meaningful intervention, and for the repercussions to be of benefit to the place and its people.

Future of Work R+D as Associate Artist

In the case of my residency for In-Situ this has been contracted as a role of Associate Artist with 24 days over 6-months, October 2019 – April 2020. Prior to this I had worked for In-Situ as a programme coordinator, as well as some freelance filming work for the Make it Pendle project, so my orientation around Pendle and discussions about The Future of Work had already begun. Even so 24 days disappear quickly and in order to make the best use of that time I opted to work remotely where possible to cut down travel and to be able to work responsively over the extended time period. This also helped to ensure that the days I did spend in Pendle were focused on engagement, artistic production and delivery rather than planning and meetings that could be done by phone or Skype.

Future of Work Workshop with Nelson and Colne College Students 2019

The sessions I delivered took place over five days at In-Situ’s base The Garage, as well as Park High School in Colne, Lancashire Adult Learning and the Leisure Box in Northlight Mill with over 100 participants. I conducted phone interviews with Pendle employers and businesses, including Dean Langton CEO of the Pendle Borough Council, and had meetings with potential partners and funders including WEA, BFiC and DWP. The artistic research involved the design and creation of the workshops, a demo for the Dreamwork: Pendle game, and an accompanying trailer or explainer video, elements of which were filmed at The Garage. I spent a large number of days ‘in kind’ reading and writing about The Future of Work and finally writing and preparing reports and articles to communicate the project such as you are reading now.

Digital Tools and the Socially-Distanced-Engaged Artist

I have found digital tools useful in making best use of the time and resources. These have ranged from the mundane, for example the use of video-conferencing software for meetings, to the more innovative and exciting including online surveys and social media to increase engagement and reach of the project, and the use of Virtual Reality in engagement sessions with young people. This embrace of technology has crept up on me slowly and caught me unaware.

When I first started working in the field of ‘socially engaged art’, and prior to that when I was still making labour intensive performance art from cardboard, it came from a desire to create ‘real’ experiences. I, alongside my Black Dogs and D.I.Y punk friends, were very heavily influenced by 60s counter-culture, the Situationist International group, and the anti-globalisation movement of the late 90s and early 2000s that critiqued ‘consumer culture’ for offering ‘spectacular’ rather than concrete experience. The underpinning thought of this milieu was that through the rupture of an authentically lived moment, ‘outside of’ the fake socialization of capitalism, a pathway to a life less alienating and boring may be opened up. This is also where the majority of my antiwork theory emerged from, as work was the dullest form of existence and as such needed to be broken from.

It was, and still is easy, to lump in the internet and virtual experiences with the spectacle, that being the process of the image of things substituting the things themselves. For this reason I resisted having a mobile phone, hand-wrote my essays and dissertation, and stayed off social media for as long as possible. My art practice was about offering a real experience where people could come together and have real conversation, as artistic analogues to the Temporary Autonomous Zones or ‘concrete situations’ of the squatting and counterculture scenes.

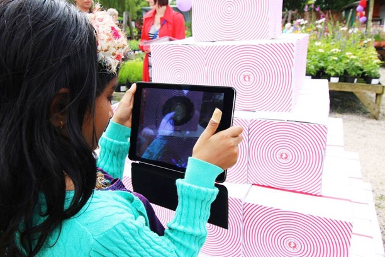

That changed for me irrevocably in 2016, however, when I was commissioned to undertake a research project about Hidden Wakefield. It became clear that the proposed engagement method I had planned using a giant pop-up pyramid to host temporary exhibitions of underappreciated aspects of Wakefield, was not going to be possible within the budget. I was invited to come up with a different solution that would engage a larger number of people for less cost and to this end I decided to use Augmented Reality to achieve a similar experience using a pyramid made from cardboard boxes and decorated with Zappar codes. When an iPad was held up to the pyramid the viewer could ‘see inside’ and reveal an image or video that represented an aspect of Hidden Wakefield.

Andy Abbott: Wakefield Centre for Dark Matter 2016

I found that the use of this technology not only made the project more practical but also more attractive to passers-by. The combination of a physical sculpture with the promise of augmented reality – this was around the time when Pokemon Go had just launched – had people swarming to engage in the art. Whilst the kids had a look around the sculpture using the iPad my team and I would have ample time for conversations with parents and other spectators about the project.

I decided to combine physical and virtual engagement in subsequent projects including Augmented Reality guided tours of Derby Silk Mill, Cliffe Castle in Keighley and Museum of Oxford, as well as the previously mentioned Lutopia project. These projects also involved a substantial online engagement component that allowed people that weren’t able to experience the interventions in real life, or make it along to workshops or creative sessions, an opportunity to experience and contribute to the project through online surveys, social media and bespoke websites.

Future of Work Workshop at The Garage 2019

Through these experiences I came to realise that my previous distaste for the virtual had been based on a reductive binary between the real and virtual, as though they were mutually exclusive. My reassessment was aided by modern technology, and the fact that a substantial section of the audiences with whom I wished to engage had grown up with the normalization of traversing the boundaries of virtual and real experience. Furthermore I now appreciate that public space is made of both physical and virtual elements and that in this conception the digital commons opens up a space for resistance to capitalist realism as effectively as any number of ‘real life events’, if not more so.

Against this backdrop I have been looking to increase and improve the quality of the digital and virtual elements of the Future of Work research project. This has involved making online versions of the workshops and creative sessions so that they can be completed by participants in their own time and in their own place, as well as used as teaching aids in group sessions. I have made use of immersive digital experiences including 360° video and worked with a digital animator to produce a trailer and explainer video for the project.

As the Covid-19 Coronavirus social distancing and lockdown measures have been enforced during the latter stage of the research project, ruling out physical engagement sessions, this attempt to try and unknot the contradiction of the socially-distanced-engaged artist could not have been more timely. For socially engaged (art) practice it is time to break the virtual/physical border.

This is Part Three of a four-part article. Part Two can be found HERE

Part Four, in which Andy overs some conclusions on the research and thoughts on 'embedded practice in a post-pandemic future', will be published here on 10th Oct 2020.